NMC and NEET PG 2025 Counselling: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Road Ahead

The National Medical Commission (NMC) is under scrutiny as NEET PG 2025 counselling begins without a clear SOP for disabled candidates. The move has sparked debates about inclusivity, transparency, and reforms in India’s medical education system.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The National Medical Commission (NMC) stands as the cornerstone regulatory authority shaping medical education and professional standards across India. As NEET PG 2025 counselling commenced in September 2025, a critical gap emerged that threatens to undermine the commission’s commitment to inclusive healthcare education — the conspicuous absence of a comprehensive Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for candidates with disabilities.

This oversight has ignited passionate debates among aspiring physicians, disability rights advocates, medical professionals, and educational institutions about the fundamental principles of fairness and accessibility in India’s medical admission framework.

Established in September 2020 through the National Medical Commission Act of 2019, the NMC replaced the Medical Council of India (MCI) with an ambitious vision: to revolutionize transparency, strengthen accountability, and democratize access to medical education.

The transition promised a modern, efficient regulatory system that would address decades-old systemic failures. However, as NEET PG 2025 counselling unfolds, pressing questions resurface about whether this apex body is successfully tackling deeply entrenched structural challenges or merely perpetuating old patterns under a new name.

This comprehensive examination delves into the NMC’s multifaceted responsibilities, the evolving complications in medical counselling procedures, the specific predicament facing disabled candidates in September 2025, and the urgent reforms necessary to guarantee equitable access to medical education for every qualified aspirant in India.

The Powerful Role of NMC in Transforming Medical Education

The National Medical Commission functions as India’s supreme regulatory authority with far-reaching responsibilities that directly impact over 600 medical colleges and hundreds of thousands of medical students nationwide. Its mandate encompasses:

Institutional Oversight and Approval: The NMC maintains rigorous standards for approving new medical colleges and monitoring existing institutions. As of September 2025, it oversees approximately 706 medical colleges offering MBBS programs and 389 institutions providing postgraduate medical education.

This regulatory framework ensures that only institutions meeting infrastructure, faculty, and quality benchmarks receive permission to train future doctors.

Comprehensive Educational Supervision: The commission exercises authority over the entire spectrum of medical education — from undergraduate MBBS programs through postgraduate specializations to super-specialty training. It establishes admission criteria, determines seat matrices, and validates the credentials of medical graduates seeking practice licenses.

Curriculum Modernization and Standardization: Setting rigorous standards for curriculum design, examination patterns, and faculty qualifications falls under NMC’s purview. Since 2020, the body has worked to align Indian medical education with international benchmarks while preserving the unique healthcare needs of India’s diverse population. The introduction of competency-based medical education (CBME) represents one significant reform aimed at producing practice-ready doctors.

Ethical Governance and Professional Standards: Ensuring ethical practices in admissions, training protocols, and professional conduct remains a cornerstone responsibility. The NMC investigates complaints of corruption, capitation fees, and malpractice in medical institutions, though enforcement mechanisms continue to face criticism.

National Exit Test (NEXT) Implementation: Perhaps the most ambitious reform initiated by NMC is NEXT — a unified licensing examination intended to replace the existing system of multiple qualifying tests. Originally scheduled for phased implementation beginning 2024, NEXT aims to serve simultaneously as a final MBBS examination, licentiate test, and NEET PG entrance exam. However, as of September 2025, its rollout faces ongoing delays due to logistical complexities and stakeholder resistance.

Since its inception five years ago, the NMC has pursued modernization with measurable outcomes: expanding postgraduate seats from approximately 35,000 in 2020 to over 65,000 in 2025, introducing transparency measures in medical college inspections, and attempting to bring uniformity to counselling procedures. Yet significant challenges persist, threatening to undermine these gains.

NEET PG 2025 Counselling: The Disability Inclusion Crisis

The most pressing controversy surrounding NEET PG 2025 counselling centers on systematic failures affecting Persons with Disabilities (PwD). As counselling began in September 2025, multiple disturbing patterns emerged:

Absence of Standardized Guidelines: Despite the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, mandating 5% horizontal reservation across educational institutions, the NMC failed to publish comprehensive SOPs specifically addressing disabled candidates before counselling commenced. This procedural vacuum created immediate confusion about eligibility verification, disability certification requirements, and the practical application of reservation benefits.

Inconsistent Medical Board Assessments: Medical boards across different states have adopted wildly divergent interpretations of disability guidelines. A candidate certified as having 40% locomotor disability in one state might receive a different assessment in another, with some boards questioning whether specific disabilities are compatible with medical practice. This lack of standardization has resulted in qualified candidates being arbitrarily rejected or their reservation status contested.

Documentation Nightmares: Disabled aspirants report being asked for multiple medical certificates, with different authorities demanding different formats. Some state counselling committees requested certificates only from government hospitals, while others accepted private medical board certifications. The NMC provided no unified format or authentication protocol, leaving candidates scrambling between various medical authorities weeks into the counselling process.

Delayed Clarifications Forcing Legal Action: The absence of timely SOPs forced numerous disabled candidates to file writ petitions in High Courts across India in August and September 2025. Courts in Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai heard multiple cases where aspirants sought directions for the NMC to clarify eligibility criteria and prevent discriminatory practices. The resulting judicial interventions, while providing relief to individual petitioners, highlight regulatory failure rather than proactive governance.

Historical Pattern of Neglect: This crisis represents not an isolated incident but a recurring pattern. In NEET PG 2022, 2023, and 2024 counselling cycles, similar issues emerged with disabled candidates challenging arbitrary seat allotment rules. The NMC’s failure to institutionalize lessons from previous years demonstrates systemic organizational dysfunction in addressing inclusivity concerns.

Specific Cases Highlighting the Crisis: In September 2025, media reports documented several heartbreaking cases: a blind candidate with exemplary NEET PG scores denied counselling participation because the system couldn’t accommodate his needs; an aspirant with cerebral palsy scoring above 500 marks forced to prove his capability to practice medicine to multiple boards; and wheelchair-using candidates being told certain specializations were automatically off-limits regardless of their academic performance or individual capabilities.

This institutional failure risks denying opportunities to deserving students who have overcome extraordinary obstacles to reach this stage. More fundamentally, it undermines the very promise of inclusivity that the NMC articulated when established in 2020.

Why Inclusivity Represents a Powerful Imperative in Medical Education

Creating an equitable system in medical admissions transcends legal compliance — it embodies a moral imperative and delivers practical benefits to healthcare delivery. Disabled candidates bring invaluable perspectives and demonstrated resilience to the medical profession that enriches patient care and advances medical practice.

Diverse Perspectives Enhance Patient Care: Physicians with disabilities possess unique insights into the patient experience, particularly when treating individuals with similar conditions. Their lived experience with healthcare systems, accessibility challenges, and societal attitudes toward disability creates empathy that purely academic training cannot replicate. Studies from Western medical schools demonstrate that doctors with disabilities show heightened awareness of patients’ psychological and social needs beyond purely clinical symptoms.

Inspiration and Role Models: Disabled doctors serve as powerful role models for patients facing similar challenges, proving that disabilities need not limit professional aspirations or competence. They demonstrate daily that medical excellence depends on intellectual capability, compassion, and dedication rather than physical conformity to arbitrary standards.

Global Standards Already Established: Leading international medical regulatory bodies have long embraced comprehensive inclusivity:

The UK’s General Medical Council (GMC) maintains detailed accessibility guidelines ensuring disabled medical students receive appropriate accommodations throughout training. British medical schools provide assistive technologies, modified examination formats, adjusted clinical rotation schedules, and workplace adaptations enabling disabled students to complete training successfully.

US medical schools operate under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandates reasonable accommodations for disabled students. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) provides extensive resources helping institutions implement inclusive practices — from screen readers for blind students to extended examination durations for those requiring additional processing time.

Australian medical schools work with disability support services to ensure barrier-free access to medical education, recognizing that diverse medical workforces better serve diverse patient populations.

India’s Constitutional and Legal Framework: India’s Constitution guarantees equality (Article 14), prohibits discrimination (Article 15), and mandates the State to make effective provisions for securing justice for disadvantaged groups (Article 46). The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, specifically requires 5% reservation in educational institutions and prohibits discrimination in admissions. The NMC, as a statutory body, operates under these constitutional obligations. Its failure to implement comprehensive SOPs for disabled candidates represents not merely administrative oversight but potential violation of fundamental rights.

Enriching the Medical Profession: Medicine demands intellectual rigor, ethical judgment, communication skills, and compassion — qualities entirely independent of physical abilities. History demonstrates that physicians with disabilities have made groundbreaking contributions: Dr. David Hartman, the first blind physician in the United States, practiced family medicine successfully for decades; Dr. Dinesh Palipana, a quadriplegic doctor in Australia, practices emergency medicine while advocating for inclusive healthcare.

India, through the NMC, must urgently adopt similar inclusive practices to ensure that the medical profession authentically reflects the diversity of the society it serves, rather than perpetuating outdated biases that equate physical difference with professional incapacity.

Systemic Challenges Undermining NMC’s Effectiveness

While the NMC has introduced valuable reforms since 2020, several structural gaps persist that undermine its effectiveness and erode stakeholder confidence:

Chronic Delayed Notifications: Last-minute guideline releases create cascading confusion among students, institutions, and counselling authorities. NEET PG 2025 counselling guidelines were published in late August 2025, leaving candidates minimal time to prepare documentation or seek clarifications. This pattern repeats annually, suggesting inadequate internal planning processes rather than unavoidable circumstances.

Interstate Inconsistencies Despite Centralization: Despite the NMC’s explicit mandate to ensure uniformity in medical education across India, counselling rules vary significantly between states. State counselling committees interpret central guidelines differently, apply varying eligibility criteria for state quota seats, and maintain different documentation requirements. This fragmentation defeats the purpose of having a national regulatory authority.

Transparency Deficits in Seat Allotment: Allegations of irregularities and mismanagement in postgraduate counselling persist year after year. While the NMC introduced online counselling platforms, the algorithms determining seat allocation remain opaque. Candidates report unexplained rank fluctuations, mysterious seat assignment patterns, and inadequate grievance redressal mechanisms when disputes arise.

Overemphasis on Single Examination Performance: Heavy reliance on NEET PG performance alone often sidelines holistic evaluation of candidates. A single three-hour examination determines the career trajectory of doctors who have completed 5.5 years of rigorous MBBS training. This approach ignores clinical aptitude, interpersonal skills, research potential, and specialty-specific competencies that predict successful medical practice better than examination scores alone.

Limited Stakeholder Consultation: Medical students, practicing doctors, and patient advocacy groups frequently complain that the NMC formulates policies without adequate consultation. The absence of PwD SOPs despite years of advocacy exemplifies this top-down approach. Meaningful engagement with disability rights organizations before finalizing counselling procedures could have prevented the September 2025 crisis entirely.

Inadequate Grievance Redressal: When problems arise during counselling, candidates struggle to obtain timely responses from NMC or state authorities. Email queries go unanswered for weeks, helpline numbers remain perpetually busy, and by the time grievances receive attention, counselling rounds have concluded, leaving aspirants with no recourse except expensive and time-consuming litigation.

Infrastructure and Technology Gaps: While the NMC launched online counselling platforms, technical glitches regularly disrupt the process. Server crashes during choice-filling deadlines, errors in seat matrix displays, and system failures during allotment result announcements have plagued NEET PG counselling for consecutive years. In September 2025, the counselling portal crashed multiple times, forcing deadline extensions and adding to candidate stress.

The Broader Picture: Transformative Medical Education Reforms India Needs

To make medical education truly equitable, accessible, and globally competitive, the NMC must embrace comprehensive reforms across multiple dimensions:

Timely and Comprehensive SOPs: Clear, detailed guidelines for disabled candidates must be published at least six months before counselling begins. These SOPs should specify exact documentation requirements, standardized medical board assessment protocols, lists of accommodations available during training, and transparent processes for resolving disputes. The NMC should collaborate with the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment to ensure these guidelines align with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.

Advanced Technology Integration: Implementing robust online grievance portals with guaranteed response timelines would dramatically improve transparency. AI-based monitoring systems could detect anomalies in counselling processes — unusual seat allotment patterns, documentation irregularities, or potential fraudulent activities. Blockchain technology could create tamper-proof records of counselling transactions, eliminating disputes about seat allotment sequences and candidate choices.

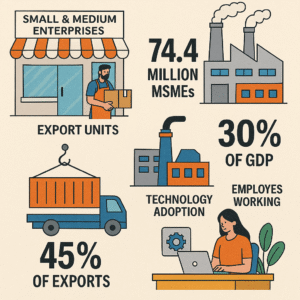

Strategic Expansion of Postgraduate Seats: While PG seats have increased from 35,000 to 65,000 between 2020 and 2025, demand far exceeds supply. Over 2.5 lakh candidates appeared for NEET PG 2025, meaning approximately 75% would not secure postgraduate seats. Aggressive expansion of PG programs in government medical colleges would reduce dependency on expensive private institutions and ensure more doctors receive specialty training. The NMC should set a target of 100,000 PG seats by 2028.

Affordable Education Guarantees: Despite regulations prohibiting capitation fees, private medical colleges continue charging exorbitant amounts for PG seats — sometimes exceeding ₹1.5 crores for three years of training. The NMC must enforce stricter penalties for violations, mandate transparent fee structures, and work with state governments to increase PG seats in government institutions where costs remain reasonable.

Faculty Development Investments: India faces an acute shortage of qualified medical teachers, with many colleges operating with faculty below prescribed standards. The NMC should incentivize experienced doctors to enter teaching by offering competitive salaries, research opportunities, and professional development programs. Faculty shortages directly impact training quality and ultimately patient care.

Holistic Evaluation Mechanisms: While maintaining NEET PG as the primary entrance examination, the NMC should explore supplementary evaluation methods. Structured personal interviews assessing communication skills, clinical reasoning tests evaluating practical judgment, and consideration of MBBS academic records could provide a more comprehensive picture of candidates’ suitability for different specialties.

Disability-Inclusive Infrastructure Mandates: The NMC should mandate that all medical colleges meet specific accessibility standards — ramps, elevators, accessible laboratories, hostel accommodations, and assistive technologies. Annual inspections should include disability access audits, with non-compliant institutions facing penalties or recognition withdrawal.

Mental Health Support Systems: Medical education’s intense pressure causes significant mental health challenges for students. The NMC should require all institutions to provide professional counseling services, stress management programs, and supportive environments that prioritize student wellbeing alongside academic excellence.

Profound Impact on Students and Healthcare Sector

The lack of a PwD SOP in NEET PG 2025 creates immediate suffering and long-term systemic damage:

Students Bear Heavy Costs: Aspirants who dedicated years to MBBS completion and NEET PG preparation face devastating uncertainty. Many disabled candidates invested in specialized coaching, traveled across India for disability certifications, and arranged financial resources for counselling processes — only to encounter bureaucratic barriers. The psychological toll of this uncertainty compounds the already stressful transition from undergraduate medical education to postgraduate specialization.

Families Lose Trust: Parents watching their disabled children being denied fair opportunities despite exemplary qualifications develop deep mistrust toward regulatory bodies. This erosion of confidence damages not just the NMC’s reputation but the entire medical education system’s credibility. When families cannot trust that merit and hard work will receive fair recognition, it discourages future generations from pursuing medical careers.

Healthcare System Loses Talented Professionals: Every qualified doctor denied admission due to procedural failures represents a loss to India’s healthcare system. The exclusion of talented disabled aspirants who could enrich the medical workforce with unique perspectives and demonstrated resilience weakens the profession. These doctors might have served underserved communities, advanced medical research, or provided specialized care to disabled patients — contributions now lost to bureaucratic negligence.

Economic Implications: India invests heavily in producing doctors through subsidized medical education. When MBBS graduates cannot access postgraduate training due to systemic failures, this represents wasted public investment. Additionally, many frustrated doctors migrate abroad seeking opportunities, creating brain drain that further strains India’s doctor-patient ratio.

Doctor-Patient Ratio Crisis Intensifies: India faces a severe doctor shortage with just 1 doctor per 1,404 people as of 2025 data, far below the WHO recommendation of 1:1,000. Denying opportunities to any qualified aspirants — particularly disabled candidates who have proven their capabilities — further widens this dangerous gap. Rural areas and underserved urban populations suffer most when doctor shortages persist.

Specialty-Specific Shortages: Certain medical specialties face acute workforce shortages in India: psychiatry, public health, preventive medicine, and family medicine. Disabled doctors might choose these specialties where their unique perspectives could prove especially valuable. Excluding them from postgraduate training perpetuates these specialty imbalances.

The Promising Road Ahead for NMC

To restore stakeholder trust and fulfill its foundational mission, the NMC must act decisively and transparently:

Immediate Actions Required: Publish a comprehensive, legally vetted SOP for PwD candidates within 30 days, applicable for all remaining NEET PG 2025 counselling rounds and future admission cycles. This SOP must specify exact documentation requirements, standardized disability assessment protocols, available accommodations during training, and guaranteed timelines for processing applications.

Ensure Interstate Consistency: Issue binding directives to all state counselling committees requiring adherence to uniform standards. Establish an NMC monitoring cell that conducts real-time audits of state counselling processes, with authority to intervene when inconsistencies emerge.

Collaborative Policy Development: Partner with established disability rights organizations like the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP), disability advocacy networks, and medical professionals with disabilities to draft truly inclusive policies. These stakeholders possess practical insights that bureaucrats alone cannot provide.

Technology-Enabled Transparency: Develop and launch a real-time seat allotment dashboard showing available seats, filled positions, and candidate rank movements throughout counselling. This transparency would reduce speculation, minimize disputes, and demonstrate the NMC’s commitment to fair processes.

Ombudsman-Style Grievance Mechanism: Establish an independent ombudsman office with authority to investigate complaints about counselling irregularities and mandate corrective actions. This office should have representation from medical professionals, legal experts, and patient advocates, ensuring balanced perspectives on disputes.

Annual Accountability Reports: Publish detailed annual reports documenting NMC’s performance across all metrics: seat expansion, faculty recruitment, accessibility improvements, grievance resolution statistics, and policy implementation progress. Transparency breeds accountability and allows stakeholders to track whether promised reforms materialize.

Mandatory Disability Sensitivity Training: Require all medical college administrators, faculty members, and counselling officials to complete certified disability sensitivity training. Many discriminatory practices stem from ignorance rather than malice. Education can transform attitudes and ensure disabled students receive the support they deserve.

Research and Innovation Incentives: Establish grants and recognition programs for medical colleges implementing innovative accessibility solutions. Rewarding institutions that excel in disability inclusion creates positive competition and generates best practices that others can replicate.

Long-Term Vision: The NMC should articulate a clear, time-bound roadmap for transforming Indian medical education into a model of excellence and inclusivity by 2030. This vision should include specific targets: 100% disability-accessible medical colleges, comprehensive mental health support in all institutions, faculty-student ratios meeting international standards, and zero-tolerance for discriminatory admission practices.

Powerful Call to Action

For India’s healthcare system to achieve robustness and meet the needs of 1.4 billion people, its medical education framework must embody three non-negotiable principles: inclusivity, transparency, and forward-looking innovation. The NMC stands at a critical juncture with the opportunity to transform the future of medicine in India — but only if it addresses the glaring gaps in policies affecting disabled candidates and all aspiring doctors with urgency and sincerity.

Medical students represent India’s future healthcare workforce. Treating them with dignity, providing clear pathways to success regardless of disabilities, and ensuring merit-based opportunities must become the NMC’s unwavering priorities.

Disability rights advocates, medical student associations, and concerned citizens must maintain pressure on the NMC through peaceful advocacy, legal action when necessary, and public awareness campaigns.

The media should continue investigating and exposing systemic failures, preventing these issues from disappearing from public consciousness.

State governments controlling medical colleges must align their counselling procedures with national standards and invest in infrastructure making institutions genuinely accessible.

Private medical colleges charging premium fees bear particular responsibility to provide world-class inclusive facilities.

Most importantly, the medical community itself — practicing doctors, faculty members, and medical students — must champion inclusivity. When the profession internally demands accessibility and fair treatment for disabled colleagues, regulatory bodies cannot ignore these voices.

The challenges facing NEET PG 2025 counselling reveal systemic weaknesses that require sustained effort to resolve. But challenges also present opportunities.

The NMC can emerge from this crisis with strengthened policies, restored stakeholder trust, and a proven commitment to the inclusive, excellent medical education system that India deserves.

It’s time for reforms that don’t merely look impressive on paper but truly empower the next generation of medical professionals to serve India with competence, compassion, and the understanding that medicine’s highest calling is healing — and healers come in every form.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on NMC and NEET PG 2025

Q1. What is the National Medical Commission (NMC) and what does it regulate?

The National Medical Commission (NMC) is India’s apex medical regulatory authority established in September 2020 under the National Medical Commission Act, 2019, replacing the Medical Council of India (MCI).

It regulates the entire spectrum of medical education in India including undergraduate MBBS programs, postgraduate specializations, super-specialty training, medical college approvals and monitoring, curriculum standardization, faculty qualification requirements, ethical practices in admissions and training, and professional standards for medical practitioners.

As of September 2025, the NMC oversees approximately 706 medical colleges offering MBBS programs and 389 institutions providing postgraduate medical education, impacting hundreds of thousands of medical students nationwide.

Q2. Why is there significant controversy surrounding NEET PG 2025 counselling?

The controversy centers on the National Medical Commission’s failure to publish a comprehensive Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Persons with Disabilities (PwD) before NEET PG 2025 counselling commenced in September 2025.

This absence created widespread confusion about eligibility criteria, disability certification requirements, documentation formats, reservation benefit applications, and specialty selection for disabled candidates.

Medical boards across different states adopted divergent interpretations of disability guidelines, resulting in inconsistent assessments where candidates received different disability percentage certifications in different states.

The procedural vacuum forced numerous disabled aspirants to file writ petitions in High Courts seeking clarity, highlighting regulatory failure and threatening to deny opportunities to deserving students who have overcome extraordinary obstacles.

Q3. How does the lack of a Standard Operating Procedure specifically affect disabled candidates?

Without clear SOPs, disabled candidates face multiple interconnected challenges: inconsistent eligibility verification across states with medical boards applying different standards;

delayed counselling participation as they scramble to meet varying documentation requirements; risk of arbitrary rejection despite meeting legal reservation criteria; confusion about which specialties are accessible versus automatically restricted;

financial losses from traveling between multiple medical authorities seeking acceptable certificates; psychological stress from uncertainty about whether years of preparation will result in admission opportunities; and ultimately, potential denial of fair access to postgraduate medical seats despite scoring well on NEET PG.

The absence of standardized protocols means that identical disability cases receive different treatment depending on which state’s counselling process the candidate enters, fundamentally undermining the principle of uniform national standards that the NMC was established to ensure.

Q4. What is the current reservation policy for disabled candidates in medical education?

Under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, Persons with Disabilities (PwD) are entitled to 5% horizontal reservation across educational institutions in India, including medical colleges.

This means 5% of seats in both government and private medical colleges should be reserved for disabled candidates across all reservation categories (General, OBC, SC, ST). The Act covers 21 types of disabilities including locomotor disability, visual impairment, hearing impairment, intellectual disability, mental illness, and multiple disabilities among others.

However, for NEET PG 2025 counselling beginning September 2025, the National Medical Commission failed to provide clear implementation guidelines for this reservation, creating confusion about how disability should be assessed, certified, and how reservation benefits should be applied during seat allotment despite the legal mandate being clear.

Q5. What critical reforms are needed in the NMC’s counselling process?

Essential reforms include: publishing comprehensive SOPs for disabled candidates at least six months before counselling begins with exact documentation requirements and standardized assessment protocols;

implementing advanced digital transparency through real-time seat allotment dashboards and AI-based monitoring to detect irregularities; ensuring absolute consistency across all state counselling committees through binding central directives; establishing independent ombudsman-style grievance mechanisms with authority to mandate corrections;

expanding postgraduate seats aggressively from current 65,000 to 100,000 by 2028 to reduce competition; enforcing strict penalties against private colleges charging illegal capitation fees; investing in faculty development to address teacher shortages; mandating disability-accessible infrastructure in all medical colleges; introducing holistic evaluation methods beyond single examination scores; and creating robust mental health support systems for students facing the intense pressures of medical training.

Q6. How does India’s medical education inclusivity compare with international standards?

India significantly lags behind developed nations in disability inclusion within medical education.

The UK’s General Medical Council (GMC) maintains detailed accessibility guidelines ensuring disabled medical students receive appropriate accommodations including assistive technologies, modified examination formats, and workplace adaptations throughout training.

US medical schools operate under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandating reasonable accommodations, with the Association of American Medical Colleges providing extensive resources for implementing inclusive practices like screen readers for blind students and extended examination durations. Australian medical schools partner with disability support services to ensure barrier-free access, recognizing that diverse medical workforces better serve diverse patient populations.

In contrast, as of September 2025, India’s NMC has not even published basic SOPs for disabled candidates, let alone comprehensive support frameworks, despite clear constitutional obligations under Articles 14, 15, and 46, and statutory requirements under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.

Q7. What is the current doctor-patient ratio in India and how do admission barriers affect this?

As of 2025, India maintains a doctor-patient ratio of approximately 1 doctor per 1,404 people, significantly below the World Health Organization’s recommended standard of 1 doctor per 1,000 people.

This shortage is particularly acute in rural areas and among certain medical specialties like psychiatry, public health, and family medicine.

The NMC’s failure to provide clear pathways for disabled candidates exacerbates this crisis by excluding qualified aspirants who could contribute meaningfully to the healthcare workforce. With over 2.5 lakh candidates appearing for NEET PG 2025 but only approximately 65,000 postgraduate seats available, roughly 75% of qualified MBBS graduates cannot access specialty training.

Any additional barriers — whether due to procedural confusion affecting disabled candidates or other systemic failures — further widen the doctor shortage gap, ultimately harming patients who cannot access adequate medical care, particularly in underserved communities.

Q8. What steps can disabled medical aspirants take if they face discrimination during NEET PG 2025 counselling?

Disabled aspirants facing discrimination should:

first, meticulously document all interactions, email communications, and rejection notices from counselling authorities;

second, file formal complaints with the National Medical Commission through its grievance portal, maintaining copies of all submissions;

third, simultaneously approach the State Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities in their state who has statutory authority to investigate discrimination cases;

fourth, contact disability rights organizations like the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People (NCPEDP) which can provide legal guidance and advocacy support;

fifth, if administrative remedies prove ineffective, file writ petitions in the appropriate High Court seeking directions to counselling authorities — courts have consistently protected disability rights when administrative bodies fail; sixth, reach out to media organizations to highlight systematic discrimination, as public pressure often accelerates official responses; and finally, connect with medical student associations and advocacy groups to pursue collective action rather than isolated individual complaints, which carries greater impact on policy reform.

Post Comment